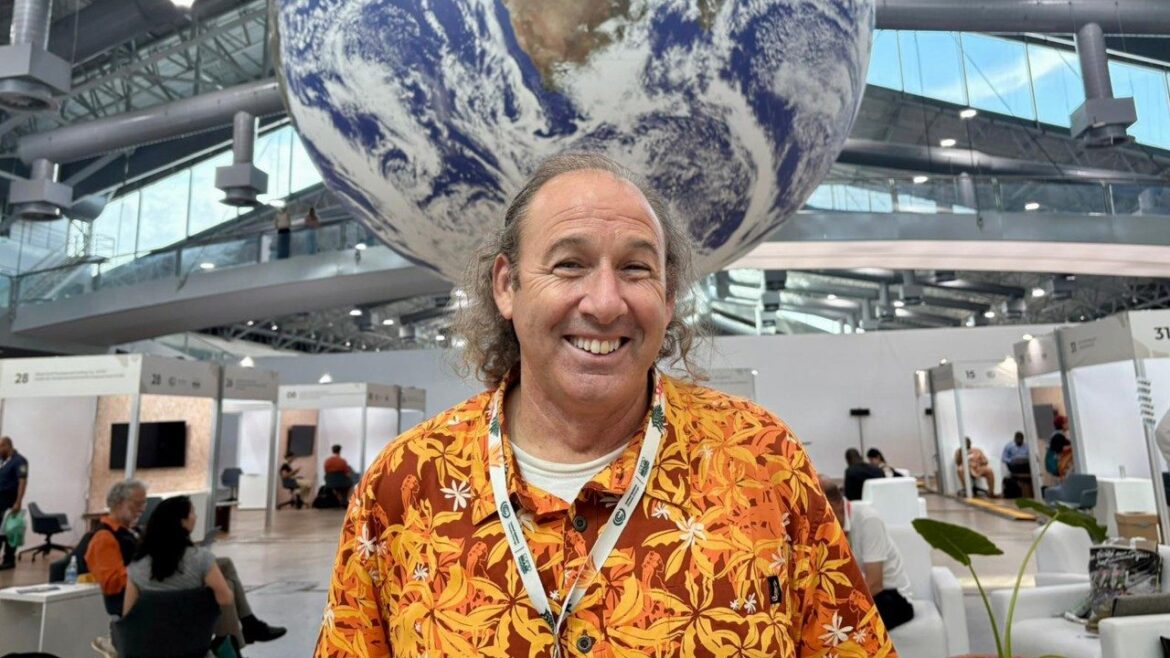

On the sidelines of the United Nations’ Conference on Climate Change, Joshua Cooper from Hawai’i warns about the differing priorities regarding climate change in the Pacific and Small Island Nations, as negotiations draw closer to a conclusion.

By Francesca Merlo – Belém, Brazil

A decade after the Paris Agreement, the 1.5°C target is interpreted in widely varying ways, meaning different things to different people. Here in Belém, during the last day of negotiations, climate diplomacy has once again collided with the lived realities of people already living the most difficult aspects of the climate crisis. Among the most compelling voices at COP30 is that of Joshua Cooper, a professor from Hawai‘i, a human rights advocate, and a bridge between Pacific Island communities and the international system.

His message is both very simple and deeply unsettling: “1.5°C is not a target. It is a lifeline. It’s life or death.”

Climate justice as a human right

Speaking to Vatican News on the margins of the conference, Cooper describes a shift he sees emerging at COP30: “There is a growing recognition,” he says, “that climate justice and human rights are two sides of the same coin. You cannot have one without the other.”

This reflection inevitably recalls a message repeatedly emphasised by the Popes over the years, most notably by Pope Francis and, more recently, by Pope Leo: justice is indivisible, and the cry of the Earth cannot be separated from the cry of the poor.”

Although the message is clear, its urgency is sometimes not grasped. In places like Hawai‘i, Vanuatu, Tuvalu, and Fiji, the “fine” lines that the world debates on paper are already destroying coastlines – along with identity, memory, and belonging. The distinction between mitigation, adaptation, and loss and damage dissolves into a more existential vocabulary: life and death, home and exile, memory and erasure.

An existential red line

The Pacific is warning us of what will inevitably happen to everyone. This week, two moments at COP acted as striking metaphors for the planet. The Moana Pavilion – the Pacific’s own space at COP – flooded during heavy rainfall. Then, a fire broke out. In both instances, Cooper says, people got just a taste of what it means to have to move uphill in a flood or lose their belongings in a fire.

“The land is not just a place you live”, explains Cooper. “It is where ancestors are buried. It is where culture exists. Asking people to move means asking them to lose everything”.

The right to self-determination – the foundational right in international law – is now all tied to every fraction of a degree.

And so, the Pacific insists that 1.5°C is not negotiable. It is not an aspiration, nor a diplomatic compromise. It is a moral threshold. Beyond it lies the irreversible loss of peoples who have contributed the least to the warming of the planet.

The wisdom of Indigenous peoples

Walking through the indigenous spaces of COP30 – the People’s COP, the Chico Mendes pavilion, the Casa Makita – Cooper reflects on a continuity of struggle since the 1992 Earth Summit, when Indigenous leaders declared: “We walk to the future in the footsteps of our ancestors”.

Indigenous chants at opening ceremonies in events such as this one, he said, contain ecological wisdom encoded over thousands of years. To modern ears, they may sound ceremonial, but in reality, they are teachings in reciprocity – daily reminders that one cannot take from the Earth without giving back.

It is a spiritual intuition that resonates profoundly with the Catholic social tradition. Pope Francis, in Laudato si’ and Laudate Deum, urges the world to recover precisely this sense of communion with creation. This vision, Cooper calls “earth democracy”.

“The climate crisis does not give you time”

In Hawai‘i, wildfires swept through Lahaina last year with terrifying speed, killing more than a hundred people. Similar tragedies have unfolded in Morocco, California, across the Caribbean, not to mention, says Cooper, that at every COP, the Philippines suffers from a typhoon.

“The fires move so fast now,” Cooper said. “You can’t prepare. Yesterday’s fire here at COP reminded us again: the climate crisis does not give you time.”

A slow process, a stubborn hope

As negotiations drag on into their final days, Cooper acknowledges the frustrations familiar to any veteran of climate diplomacy.

“It’s not enough. It’s not fast enough”, he admitted. “But you don’t give up. You push. You fight for principles. And you build alliances”.

COPs, he said, are not merely conferences but wonderful moments of encounter. On flights, in hotel lobbies, at cafés in the city, unexpected coalitions form – between academics from Cambodia, activists from Fiji, elders from the Amazon, students from across the world.

Many become, as Cooper puts it, “friends you simply hadn’t met yet”.

Looking ahead: a critical COP31

Cooper then turned to what he described as the “funky Frankenstein” emerging around next year’s COP: a last-minute, three-part arrangement in which Turkey will host, Australia will preside, and a separate Pacific-focused segment may take place in Fiji. For Cooper, the hybrid structure exposes a deeper issue – “everyone thinks they got what they wanted,” he said, “except the Pacific, who once again have to fly the furthest, stay the longest, and return home days after everyone else.”

He lamented the missed chance to bring the world closer to the climate frontlines, recalling proposals for Adelaide or even Tasmania as potential sites that could have allowed Australians to confront the crisis “up close”, the way bushfire images once stirred the country’s conscience. Hosting, he insisted, is not merely logistical; it is a test of civic space, of willingness to hear Indigenous defenders, of a nation’s capacity to ensure that those most affected are safe and seen.

Still, Cooper remains determined. However unconventional the structure may be, he said, “we will make the most of whatever exists.” In a process often driven by states, his reminder was quiet but firm: that it is still “we, the peoples” who must carry the moral weight of climate action forward.

A call to conversion

Cooper’s reflections echo the moral challenge Pope Francis often called on the global community to take up, and that is reiterating that the climate emergency is not only scientific and political; it is spiritual and requires conversion – in lifestyle, in governance, and in the way nations relate to the most vulnerable.

“We vote three times a day with what we eat,” he said. “And again at the ballot box.”

The future, he believes, lies in embracing what Indigenous peoples have never abandoned: a worldview rooted in reciprocity, memory, and care. It is, he said, not a new direction but a return to an older, wiser one.

Listening, learning, leading

Cooper summarised this way forward with three words: Listen, learn and lead.

“Listen to those on the frontlines. Learn from their resilience and their wisdom. Then lead – with conscience, courage, and compassion”, he said.

As COP30 draws to a close, the Pacific’s plea is to recognise that their struggle is the world’s future, and his hope is that the world will listen.